JPhoto

Those were the days my friends when we were called the Gang of Eleven. Eleven street boys from deep in the bowels of Chicago’s north side. City boys, rough-necks, street dogs. We were called all those names. We didn’t care. Lakeview, Wrigleyville, Addison street were our haunts. Infamous Clark street was filled with hippies, flower children, beaded girls with long dresses, bell bottomed jeans, and long, long hair. Stores had

incense smells, like sandalwood, frankincense and myrrh wafting in the air as my friends and I walked down the street taking it in as if it were a historical event. An East Indian restaurant used strong curry spices filling my nostrils with these powerful, yet delicate odors.

The sidewalks were shared with older, drunken Vietnam Vets living on the street, sometimes mumbling into their grimy shirt collars, sleeping in secluded doorways on newspapers and flattened boxes, wrapped in their green army jackets with their name patches giving them identity when passersby eyes look the other way, covered in a filthy tossed off surplus sleeping bags unable to return to normal after time spent killing during a rainy season’s surprise ambush by Viet Cong underground cave dwelling soldiers, smoking opium, and eventually, passing into a point of no return.

These older kids sat on street corners passing joints, playing music, drumming, singing and dancing like Native American Indians around a ceremonial campfire waving their arms up in the air, while swaying back and forth as if they were under the spell of a witch doctor or shaman.

We were in Mr. D’s class all day because the principal didn’t want us moving from class-to-class, since he said we were “too disruptive”, and the teachers “would lose control of the room when we were in there.” School was cool. It was better than being on the street all day. We did learn. We all were good readers, and as a class, would write stream of consciousness collective stories taking turns creating crazy sentences.

He made us each stand up at the knife scarred and use-warn ancient blackboard with the thick oak tray filled with yellow, pink, red, blue, green and white chalk and write our own sentence using the color of our choice, and then read it aloud facing our classmates with the same pride as delivering the State of the Union address. We did this more than once a week with the same excitement as when we would get an A on our spelling test.

Mr. D would take us outside as often as he could. A large grassy field with trees lining the boundary was behind the school. We played softball in every type of weather. We all were Cubs fans. In the summer, I would ride my bike over to the ball park and listen to Jack Brickhouse call the games. On May 12, 1970, I cut school, and rode my bike to the ball park, and sat on the North Clark street curb, close to home plate, when I heard the crowd explode with joy after Ernie Banks hit his legendary 500 home run. “Jarvis winds away. That’s a fly ball, deep to left. Back, back, hey, hey, he did it! Ernie Banks got number 500!”

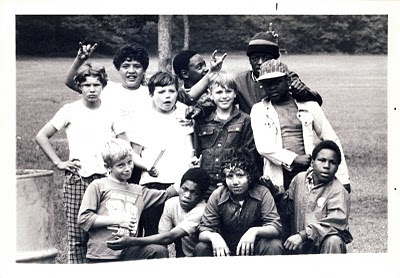

That moment remains as vivid in my mind as the day Mr. D had us celebrate a few days later, when the sky turned bright blue, and air was summer warm, out behind the school, we partied. Tony put his whole face in the cream pie. We came together as brothers, enjoying our bond, as Mr. D snapped a picture.

by, J

(Entries must be 600 words or less.)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.